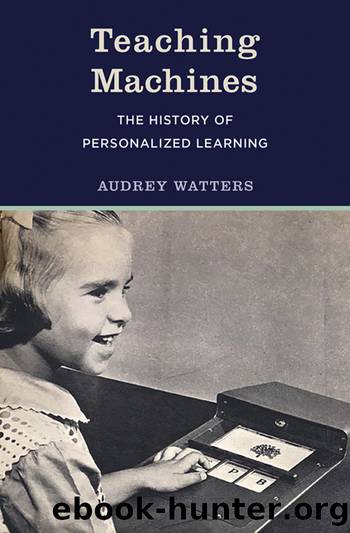

Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning by Audrey Watters

Author:Audrey Watters [Watters, Audrey]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: education, Computers & Technology, history, Technology & Engineering

ISBN: 9780262045698

Google: 7uo2EAAAQBAJ

Publisher: MIT Press

Published: 2021-08-03T00:26:09.037550+00:00

And it wasnât just Kâ12 students who were learning faster. The same article said that âIBM has been able to reduce from fifteen to eight hours the class time needed to cover the opening sections of a course the company gives on the use of its 7070 computer.â The research was overwhelmingly positive, according to the press coverage. âExperimenters also report, as a rule, that students like programmed instruction and think it does them a lot of good.â28 As a ruleâthat is, there was no other way to think about the future of education than as one that would be programmed in this way.

That teaching machines worked better and faster than human teachers was certainly a story that appealed to the readers of business magazines, which seemed more than happy to repeat a story that derided the school system for its backwardness, its inefficiencies. This stance had found a friendly audience in the business community at least since the publication of Frederick Taylorâs The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911. (This was the observation Raymond Callahan made in 1962 when he published his book Education and the Cult of Efficiency on the efforts in the early twentieth century to run schools like businesses.29) In a 1958 article, Fortune complained of âThe Low Productivity of the âEducation Industry,ââ blaming teachers and teachersâ unions that the âoutputâ of schools had not kept pace with investment.30 Opening with the cliché that education was âbig business,â Fortune columnist Daniel Seligman sneered that teachers âoppose anyone who tries to apply business concepts to their work. The concept of productivityâi.e. output in relation to inputâis especially abhorrent to educators, possibly because most productivity figures tend to make the education âindustryâ look bad.â31 Teachers, Seligman contended, were so inefficient, they had no right to demand an increase in pay. Suggesting that in previous decades, schools were actually more productiveâin part because of larger class sizes, he claimed that âthirty years ago students were educated more âefficientlyâ than they are today, i.e. each student required fewer teaching man-hoursâand fewer administrative, clerical, and custodial man-hoursâthan he does today. There is now one teacher for every twenty-six students, in 1928 there was one for every thirty students, and in 1900 there was one for every thirty-seven.â32 New technologies were going to change this, Seligman arguedâwhether teachers liked it or not. Mocking the teachersâ unionsâ concerns, he likened their stance to âthe locomotive firemenâs unionâs early reaction to the diesel engine.â33

To underscore how educational technologies were positioned to displace teachers, Seligman touted the adoption in 1956 of television-based education in Hagerstown, Maryland, âwhere 18,000 pupils, from the first through the twelfth grades, are receiving some instruction by television. The instruction is transmitted on a closed circuit from six âstudiosâ in Hagerstown at the rate, currently, of 120 sessions per week, to 450 classrooms equipped with conventional 21-inch black-and-white table models.â34 The cost savings, Seligman argued, indicated that âclassroom TV is certain to pay for itself at the very leastâ by rendering teachers in the district superfluous.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Exploring Deepfakes by Bryan Lyon and Matt Tora(8361)

Robo-Advisor with Python by Aki Ranin(8305)

Offensive Shellcode from Scratch by Rishalin Pillay(6426)

Microsoft 365 and SharePoint Online Cookbook by Gaurav Mahajan Sudeep Ghatak Nate Chamberlain Scott Brewster(5673)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5398)

Management Strategies for the Cloud Revolution: How Cloud Computing Is Transforming Business and Why You Can't Afford to Be Left Behind by Charles Babcock(4562)

Python for ArcGIS Pro by Silas Toms Bill Parker(4499)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4284)

Elevating React Web Development with Gatsby by Samuel Larsen-Disney(4221)

Liar's Poker by Michael Lewis(3435)

Learning C# by Developing Games with Unity 2021 by Harrison Ferrone(3350)

Speed Up Your Python with Rust by Maxwell Flitton(3307)

OPNsense Beginner to Professional by Julio Cesar Bueno de Camargo(3275)

Extreme DAX by Michiel Rozema & Henk Vlootman(3256)

Agile Security Operations by Hinne Hettema(3187)

Linux Command Line and Shell Scripting Techniques by Vedran Dakic and Jasmin Redzepagic(3169)

Essential Cryptography for JavaScript Developers by Alessandro Segala(3137)

Cryptography Algorithms by Massimo Bertaccini(3082)

AI-Powered Commerce by Andy Pandharikar & Frederik Bussler(3036)